Back when I was a young man, a long time ago, growing up on the Coalfields of Northern NSW, seeing decent music meant making a journey to Sydney or occasionally to Newcastle. The pubs in Kurri Kurri, Weston and Abermain would often have live music but, in most instances, the music would be a singer guitarist or a duo playing covers of popular late seventies tunes that would be described as ‘West Coast’, as in the west coast of the United States – covers of songs by the Eagles seemed to be something I remember. Sometimes a touring Australian band might make an appearance at one of the clubs like the Weston Workers Club but in large these were bands who were neither hugely popular nor alternative and it seemed that many of the locals judges the quality of a band by their willingness to do a cover of Cold Chisel’s Khe Sanh – I can hear the ocker accented call of ‘da youse know Khe Sanh’ called out more than once by a mulleted young man in a chequered flannelette shirt (long before such shirts became a symbol of hipster grunge), straight legged Amco or Lee Cooper jeans and desert boots, often with a packet of Winfield cigarettes in the rolled up sleeve of the flanno.

When I was twenty, I moved to Newcastle and then to Sydney and then back to Newcastle and immersed myself in music spending nights in small rooms listening to new and interesting bands and by time I turned twenty-three, I had a regular gig mixing bands at Newcastle University and recommending bookings to the activities officer at the student union. One of my favourite band at the time were the Falling Joys and I managed to get them booked a number of times. Two of my favourite bands of all time, the Go-Betweens and the Triffids had, by then primarily relocated to London. Another band that blew me away with their unique sound and lyricism was Not Drowning Wave and it was a delight to meet members of the band when they played at the uni in the late eighties following my recommendation to book them.

Imagine then, how strange it seemed to drive back to the Coalfields on a cold night in Winter to hear David Bridie, lead singer and songwriter for Not Drowning Waving play a solo gig at the old Denman Hotel in Abermain.

This is Just a Coal Town

David Bridie also led another band that became more popular than Not Drowning Waving and that band was My Friend the Chocolate Cake. One of the songs he played at his solo gig in the Coalfields was The Gossipfrom the Chocolate Cake album Brood. The first time I heard this song back in the early ‘nineties, I thought that he could have been writing and singing about my Coalfields with the opening lines of the song ‘This is just a coal town, and all the people there are sheltering from the cold winds on the crest of the big bleak hill’ could be a description of Kurri Kurri in late winter when the westerly winds are howling down Lang Street. He wasn’t writing about Kurri Kurri and he said at his recent concert that this was the first time he had been to the Hunter Valley. I don’t know what town he was referring to, but I suspect, given David Bridie is from Melbourne, the town might have been one of those towns in the Gippsland Coalfields – towns like Wonthaggi and Korumburra – and this is reinforced for me by a reference in the song to it being a town that ‘they make films about’ which immediately brought to mind Richard Lowensteins brilliant movie Strikebound about a pit lock-out in the early nineteen thirties.

Writing the South Maitland Coalfields

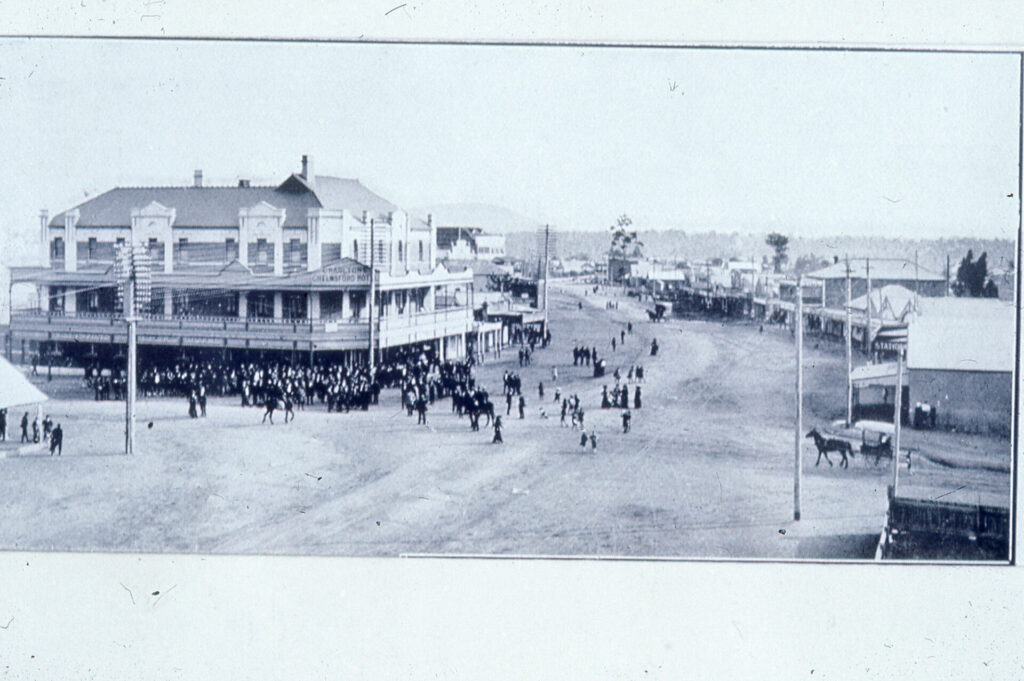

If you look through historical records, there was a lot of cultural activities on the Coalfields in the first half of the twentieth century and these, to a large degree, had vanished by time I was growing up in the sixties and seventies. There were no brass bands that I can remember, no musical or debating societies, no drama groups or adult amateur theatre. There was, I recall a pipe band that may have been based in Abermain or maybe Kurri Kurri and I remember seeing our neighbour heading off to various marches and events in his kilt and sporran.

Why the demise of a richness of cultural practice? I think there were a number of causes. In the early part of the twentieth century, the towns that form a long connected ribbon along the South Maitland Railway grew up close to coal mines with one or two mines associated with each town and, as these mines gradually closed (the last one near Weston was Hebburn No 2 that closed in 1973), the worker started to move further afield for jobs with many heading to the coal mines around Lake Macquarie and other people heading to the industries in Newcastle. Television arrived in 1962 and, perhaps, even earlier for those who could afford to buy both a television and thirty or forty-metre-high mast antennas that could pick up reception from Sydney and culture than became something that was consumed at home and certainly not something that was created. Interestingly, whilst culture disappeared, sport never did and towns like Weston and Kurri Kurri have had championship winning teams in different sports for many years.

Telling the Stories

There were always writers on the Coalfields but not a strong history of publication. Jock Graham was a writer who published a couple of volumes of poems and at least one novel in the forties and fifties and I remember my grandfather, a militant communist, being very fond of the poem Blood on the Coals.

More recently I have been excited to read work by a Coalfields poet, Greg McLaren. I was mesmerised by The Kurri Kurri Book of the Dead with its poems about things that were so familiar to me and it was strange to read of the streets I walked as a child and young man rendered in such a way that I was seeing them through my own eyes and the eyes of this poet and those visions weren’t always aligned but, at other times were spot on. Greg’s most recent work, Camping Underground has a different effect altogether – the physical landscapes he writes about are familiar, the bushland around Cessnock and Kurri, the towns themselves and their inhabitants but there is also the unfamiliar but frighteningly possible – an Australia descending into a dystopian hell of far right lunatics, military coups, death squads and communities locked down because of a pandemic. If you are interested in modern Australian Poetry and the culture of the Coalfields click on the links to purchase these great books.

Writing the Ordinary

It seemed somehow fitting to be able to sit in the back room of a pub that was both familiar and strange to me (it has been more than forty years since I last had a beer here and it has recently changed its look dramatically becoming a quirky music venue called Qirkz) listening to music that was also both familiar and strange, particularly the Not Drowning Waving Tracks that on record were complex and multi-layered with a wide range of instruments being stripped back to just a piano and David Bridie’s voice. I was entranced with the magic of what I was listening to and where I was and, in the silence between songs, I sometimes could remember or maybe imagine the ghost like whistles of the steam trains of my youth making their way through the Denman cutting, just over the road from the pub.

David Bridie’s songs are sometimes about every ordinary things and sometimes they are epic but, in the end, they are always human, they are stories of life and of people and of struggle and of sometimes buggering it all up. It was good to hear these songs on my old country and brought a degree of nostalgia and a desire to want to capture more of the stories of the Coalfields, my own, perhaps, foundation myths.