Perhaps it was something speaking in the wind that was whipping off Macquarie Harbour or perhaps it was something about the guilty pleasure of cruising up the Gordon River on the top deck of the tourist boat, sitting in airline style chairs, eating gourmet food, drinking Tasmanian wines (some of the Rieslings are my favourite of all wines), but I started to think of Tasmania as a haunted place a place where there is so much beauty and so much pain. Perhaps it was the desolation of Sarah Island, perhaps it was the knowledge of the attempted genocide against the original inhabitants (and the myths and lies we were told in primary school that there were no longer any Tasmanian Aborigines and they had all died out in the nineteenth century). Perhaps it was because the European history is one of exile and displacement that has not entirely gone away.

George Augustus Robinson

When I was in High School, I read Robert Drewe’s book, The Savage Crows (Collins, 1976) and the battered red covered paperback still sits on my bookshelves next to a number of books by Robert Drewe. He may well have been one of the first contemporary Australian writers that I had read as a young adult that had not been a prescribed reading in English. Of course, there were other Australian writers on my Higher School Certificate who I learned to appreciate much later and whose books I have avidly collected in first editions, writers such as Randolph Stow and Patrick White. The Savage Crows was Drewe’s first novel and tells the story of the government Aboriginal Protector, George Augustus Robinson and the exile of Tasmanians to Flinders Island where many Aboriginal women were kept as sexual slaves by mutton birders and sealers while, at the same time telling the story of the mental unravelling of a young man researching and writing about this time in history. My 1976 edition maintains, on the back cover blurb, the fiction that this is ‘an historical account of the extinction of the Tasmanian Aborigines …’.

Almost as a book end, but not quite because I will continue, I’m sure, to devour books by Tasmanians or set in Tasmania, a fictionalised George Augustus Robinson is a key character in Jock Serong’s latest novel, and the third part of a trilogy, The Settlement, published last year. Robinson also features in one of my favourite writers, Richard Flanagan’s book, Wanting. So, who is this Robinson? Robinson was a colonial administrator and a self-trained preacher who lived from 1791 to 1866 and was responsible for a policy that, these days, would be called ethnic cleansing. His story is at the dark heart of race relations in Tasmania and while there was once a view that he was a missionary determined to save the lives of Tasmanian Aborigines and who was responsible for recording so much of their culture, he was also instrumental in destroying that culture and, by the forced removal of people to Flinders Island, also destroyed the connection between people and country.

‘How do we taste, it’s a curious place, a mountain to resort to customs of the sea.’ The Drones

I had heard of Alexander Pearce before I visited Sarah Island at the beginning of 2023. His ghost also hangs like a spectre across Tasmania and he pops up from time to time in cultural references. Sara Island was a prison for intractable convicts who had been sentenced for further offences in Hobart. It is located on the west coast in Macquarie Harbour and was early Australia’s version of a Siberian Gulag. It must have appeared completely inhospitable to those first Europeans with treacherous waters and mountains that appear to be impenetrable, hundreds of miles over the rugged south west to Hobart.

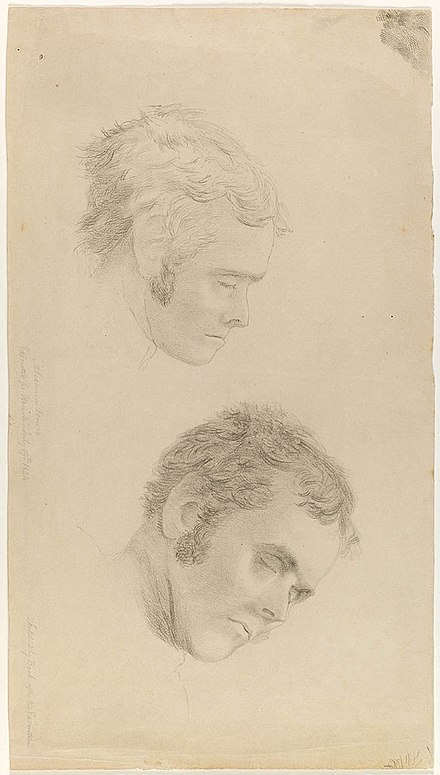

I first read his fictionalised story in For the Term of His Natural Life by Marcus Clarke (published in serialised form 1870-1872) while I was studying Australian Literature at university. Pearce also is mentioned in the Drones’ song ‘Words from the Executioner to Alexander Pearce’ on their album Gala Mill (see here for the clip of the song). I later read about the real Alexander Pearce in Robert Hughes’ The Fatal Shore and he has also been featured in the films The Confession of Alexander Pearce and Van Diemen’s Land and in the horror film Dying Breed.

Alexander Pearce was one of the few people to escape from Sarah Island and, in fact, escaped twice. The first time, he escaped with seven other prisoners and, at some point, overtaken by hunger, they made the decision to kill and eat the slowest member of the group. The cannibalism continued for many weeks until there was only Pearce and another convict, Greenhill, and it was Greenhill who had possession of the only axe the group had. It was a matter of who fell to sleep first and after a couple of days without sleep and desperately hungry, it was Greenhill who nodded off and was killed and eaten by Pearce. Pearce made it all the way across the most rugged country in Tasmania and was taken in by some bushrangers in the midlands to the north of Hobart. He confessed to the cannibalism to the magistrate and gaol chaplain who did not believe him and thought that Pearce was covering for his mates who were still at large and so he was sent back to Sarah Island. He escaped a second time with a young man who he quickly killed and dismembered. It was thought that he had developed the taste for flesh because, unlike the first escape across the mountain where there was not a lot of edible vegetation and little wildlife (and for which they didn’t have weapons to kill fast moving prey like wallabies), on the second attempt he headed up the coast where there was abundant fish and molluscs and bush tucker to be had. When he was caught the second time, Pearce was hanged in Hobart.

Tasmanian Gothic

Tasmanian Gothic is a term that has emerged in recent years to describe books, film and television that share elements of traditional gothic story telling transported to a Tasmanian landscape. In television, the one of the best examples is The Gloaming This series was made by the same filmmaker who also made The Kettering Incident which is also considered to be a good piece of Tasmanian Gothic television.

It is almost impossible not to think of Richard Flanagan when one thinks of contemporary Tasmanian writing. The dark history of the island, its ghosts and a sense of unfinished business resonate in just about everything of his that I have read. Flanagan is critically acclaimed and won the Booker Prize in 2014 for his magnificent book The Narrow Road to the Deep North. It was interesting to travel around Tasmania and to see Flanagan’s books for sale everywhere – in gift shops, in museums and tourist attractions and other places where you would not normally expect to see literary fiction. I have been reading Flanagan for many years, beginning with The Death of a River Guide in 1996 (it had been published in 1994 but I read the first paperback edition). From that moment I was hooked, and I have never been disappointed by any of his work and they rank amongst my favourite books written in Australia.

There is a strong elegiac character in Flanagan’s work that is also life affirming and never becomes melancholic and this seems to be very Tasmanian in its nature as if everybody who creates there is somewhat in awe of the majesty of the landscape, the remoteness and the dark history. Gould’s Book of Fish has been described as the most ‘Tasmanian Gothic’ of Flanagan’s works but the same could also be said of Wanting. Both of these books are set in the nineteenth century with much of Gould’s Book of Fish being set on Sarah Island while parts of Wanting, like The Savage Crows, is set in the islands of Bass Strait. There is a dream like quality to Gould woven into the horror of the experience of Sarah Island and the end of the book is stunning.

Not quite in the gothic tradition but certainly delving deep into the darkness of Tasmania are the three books that comprise the trilogy by Jock Serong, mentioned above. Serong is not a Tasmanian by birth and spent many years on the south west coast of Victoria (a place with its own sense of a dark history, isolation and rugged beauty) and now spends time, according to his website, living on Flinders Island. These books do not shy away from the darkness at the heart of the soul of this country and the mistreatment of people at the hand of the conquerors but they also celebrate the indomitable nature of the human spirit that has seen a First Nations culture survive despite many efforts to destroy it.

Divining the Truth

Australia is a nation that likes to remember its dead but in a very selective manner and in that remembering we like to create national myths. In some quarters, the bushranger Ned Kelly is seen as an anti-authoritarian hero and not as a semi-literate disaffected son of a migrant who started life as a horse thief and ended up killing three police men and somewhere in the middle lies a sort of truth. We celebrate Anzac Day and remember the brave soldiers who volunteered to defend their country and grant us the freedom we enjoy today and don’t speak of Anzac in terms of us being the invaders in a war a long way from our shores fought by young men who had no idea why they were killing Turks who were defending their own shores. What then, is the purpose of writing? It is not necessarily in order to debunk the national myths (although a good deal of debunking should occur). In one of his speeches, Richard Flanagan wrote that the role of the writer ‘in one sense is the very real struggle to keep words alive, to restore them to their proper meaning and necessary dignity as the means by which we divine truth’ (Seize the Fire – Three Speeches – Penguin 2018).

I called this blog Tasmanian Books of the Dead because many of the books I have mentioned have allowed the dead of the past to be given new voices, whether they be historical figures or fictional characters hewn out of the history and the landscape and the words that others have left. It is hard not to spend any time in Tasmania, particularly if you have read any of these books or read any of the fine histories of Tasmania and not feel these ghosts speaking to you.